In late 1918, both the UGCC hierarchy, headed by Metropolitan Archbishop Andrey Sheptytsky, and parish clergy enthusiastically welcomed the creation of the West Ukrainian People’s Republic, actively participating in its construction. Priests were part of its administrative authorities (for example, as district commissioners); they joined the propaganda campaign for Ukrainian statehood and supported the newly formed state and army from the pulpit (for example, urging congregations to join the Ukrainian Galician Army (UGA) and the fight against Poles).[1]

In 1918, the Greek Catholic Church in Galicia administratively separated into the Lwów (today Lviv) archdiocese and the Stanisławów (now Ivano-Frankivsk) and Przemyśl (Ukr.: Peremyshl) dioceses. At the top of the hierarchy was Metropolitan Sheptytsky, who enjoyed absolute authority among Ukrainians; the bishops of these dioceses were Hryhoriy Khomyshyn and Yosafat Kotsylovsky, respectively. It is important to remember that the Church emerged weakened from the war: Metropolitan Sheptytsky returned to Lwów only in 1917, while the authorities of the Przemyśl eparchy also returned the same year, having been refugees in Moravia.[2] Since many parishes had been devastated, with buildings destroyed or dismantled by the marching armies, the priests’ first task was reconstruction, yet most chose a different course, prioritising their obligations to the nation.

The Polish authorities responded to this stance adopted by the Greek Catholic clergy with reprisals in the form of arrests and, subsequently, internment of some priests in camps or confinement.[3] The Polish authorities had used internment against the opposition since the beginning of the conflict, starting with members of the Ukrainian National Council in Przemyśl (Dr Teofil Kormosh, Dr Volodymyr Zahaikevych and others), arrested by Polish troops on 11 November 1918 following the capture of left-bank Przemyśl and from 18 November incarcerated in a camp in Dąbie, outside Krakow.[4] Although the majority of the tens of thousands of Ukrainian nationals held in Polish camps in 1918–1921 were UGA soldiers, the civilians, numbering a few thousand, represented a cross-section of Galician society – from top politicians, national leaders (such as Prof. Kyrylo Studynsky and Dr Volodomyr Starosolsky), through clerical and lay intelligentsia, to workers and even simple peasants. They were interned in several camps, the main one being Internee Camp No. I in Dąbie, near Krakow (today part of the city); some civilians also ended up in Prison Camp No. 1 Strzałkowo (in Greater Poland), as well as in camps in Wadowice, Brześć-Litewski, Tuchola, Modlin and Dęblin.

The internments were conducted by the Polish Army (specifically the military police). The reasons given in documents can be divided into several categories. Priests were often accused of participating in the construction of the West Ukrainian People’s Republic (ZUNR); such charges were levelled, for example, at Fr Hryhoriy Muzychko, a catechist in Żurawno (Zhuravno). Under Ukrainian rule, he was the commissioner for the town and allegedly “caused acute trouble to the Polish population” by harassing them, especially in terms of food supplies.[5] The priest did not confess to the charges against him, but this did not prevent him from being interned in Strzałków, where he spent several months in summer and autumn of 1919. A hostile approach to Poland and Poles was a common accusation. This was the pretext for the detention of Fr Ilya Klyvak (on whom more below) as well as Fr Petro Petrytsky from the parish of Kołokolin (Kolokolyn) in the Rohatyn municipal district, who was interned in Lwów as a result of refusing to issue the birth certificates of Greek Catholic conscripts and ignoring government decrees concerning use of language.[6]Clergy were also accused of agitation for the Bolshevik cause – as in the case of Fr Amvrosiy Tumanovych – or the Ukrainian cause. Fr Natal (Aital) Kovalsky was charged with the latter after singing the song Mnohaya lita during a church service, for which he was arrested.[7] Adam Szczupak correctly notes that the Polish authorities justified the mass internment of UGCC priests by arguing that it was essential to remove the most ardent political activists and anti-Polish agitators,[8] as is evident in the cited examples.

It is valid at this point to ask about the scale of the Polish authorities’ internments of Greek Catholic priests. Information disseminated by Ukrainians in 1919 gave a figure of as many as 600 interned clergy.[9] Meanwhile, the Polish foreign ministry, in a memorandum from January 1920 addressed to the Holy See and based on lists presented by the dioceses, stated that only 24 priests were interned in the Stanisławów eparchy and 36 in the Lwów jurisdiction, giving a total of 60. The Przemyśl diocese did not submit a list, but the figure was apparently “significantly lower”.[10] Yet this data is dubious – it probably refers to the figure at the time, corresponding to the end of 1919 and beginning of 1920, by which time the majority of people had either been released or were confined. This is corroborated by a Foreign Office letter to the liaison officer from 19 December 1919 requesting data concerning those interned, priests in particular.[11] The Polish authorities therefore presented the minimum number of people in captivity, which was not an accurate figure. At this time, Ukrainians were preparing lists of the victims of persecution, one of which was included in the Bloody Book (Кривава Книга) and subsequently reprinted in Fr Ivan Lebedovych’s monograph Полеві духовники УГА, published after his emigration.[12] This directory gave the names of 372 priests interned or arrested by the Polish authorities, along with 44 Basilian monks, six clerics, and 43 nuns, noting that there were more internees. Is this list credible? Many of the priests named were indeed sent to camps, but they are conflated with those who were in prison or only confined in their hometowns or in Lwów. Meanwhile, Liliana Hentosz writes that in autumn 1919 there were around 500 Greek Catholic priests in Polish camps and prisons, and according to the Przemyśl diocese itself there were 165 priests.[13]

The only solution is therefore to examine the cases of individual priests, counting those documented as having spent time in prison camps. The matter is additionally complicated by the fact that not all interned priests ended up in camps. Many were arrested and immediately confined in a place other than their own parish, without later incarceration. One such case was that of Fr Vasyl Yaremkevych, the parish priest in Wowcze (Vovche), interned on 14 July 1919 and then confined in Sambor (Sambir) until 2 August, before returning, still confined, to his parish.[14]

After counting all the people for whom I found documents confirming their imprisonment in camps or internment in Lwów or other places, I can put their number at no fewer than 170 members of the Greek Catholic clergy (120 diocesan priests and 42 Basilian monks). To this figure we must add 24 clerics from the Red Ukrainian Galician Army, disarmed by the Polish Army in Greater Ukraine in April–May 1920 and interned in the Tuchola camp.[15] The actual figure is probably higher: according to the calculations of UGCC historian Adam Szczupak, during the Polish-Ukrainian War, i.e., between November 1918 and July 1999, the number of interned, arrested or confined Greek Catholic clergy amounted to around 400 people. Not all of them, however, had internee status.[16]More research is needed on this subject.

All Church personnel were sent to camps: from lecturers at theological colleges and chapter canons such as Dr Constantine Bohachevsky, Przemyśl cathedral parish priest, to parish clergy, Basilian fathers, and seminarians. Most priests were imprisoned at the camp in Dąbie as well as the separation station at the Brygidki prison in Lwów, while others were sent to Wadowice and Strzałków, and in smaller numbers also to Modlin, Pikulice, Brześć, Jałowiec and Tuchola. Two UGA military chaplains were incarcerated in Tuchola (Fr Ivan Luchynsky from Lwów, probably from the St George’s Cathedral chapter, and Dr Teofil Chaikivsky from Wolostków (Volostkiv[17]), as well as the aforementioned clerics. In late November 1920, Prime Minister Wincenty Witos demanded their release; this ensued two months later, and the clerics were allowed to return home and continue their studies.[18]

From the beginning of the Greek Catholic priests’ imprisonment, efforts were made to secure their release. Metropolitan Sheptytsky and Bishop Kotsylovsky intervened with the Polish authorities in this matter in early 1919. The West Ukrainian authorities also took action. In March and April 1919, the ZUNR National Foreign Affairs Secretariat informed their Polish counterparts that they had released all interned Roman Catholic priests and expected the Poles to follow suit with Greek Catholic priests.[19] And indeed they did: on 14 April 1919, most of the priests behind the fences of Dąbie and Wadowice were freed to allow them to spend Greek Catholic Easter in their parishes. In summer 1919, the Vatican joined the fray. Papal Nuncio Achille Ratti endeavoured through both official and private channels to improve the situation of the captive Greek Catholic priests. On 20 July 1919, he wrote to General Haller, highlighting the difficult situation of the interned Greek Catholic priests as well as the brutal treatment of 42 Basilian monks,[20] and in late July he wrote to General Leśniewski, pointing to the tough living conditions in the camps as well as the situation of the priests held in Lwów. In response, Leśniewski issued an order permitting the interned Greek Catholic clergy to celebrate the liturgy in their places of isolation and civilians to participate.[21] On 19 August 1919, Ratti again brought the matter of arrested and interned Ukrainian priests to the general’s attention. Among his requests was the release of those held in camps, especially the Basilians from Dąbie. The papal nuncio argued that the monks were denied the possibility to live their lives in accordance with their calling. Through Ratti, they asked to return to Krechów (Krekhiv) and Żółkiew (Zhokva). In response to their requests, an enquiry began on 24 August.[22] The nuncio returned to these matters in November 1919, when Fr Leontiy Kunytsky travelled from Lwów to Warsaw. He visited both Ratti and Józef Piłsudski, Poland’s Chief of State, as well as the minister of religious denominations and public education, Jan Łukasiewicz. According to Kunytsky himself, the nuncio was very prejudiced towards the Ukrainian clergy and blamed the situation on them, but he came around and asked Kunytsky for the relevant materials. Piłsudski, meanwhile, promised to deal with the matter, but stressed that it would be difficult.[23] The Greek Catholic priests still imprisoned in camps repeatedly applied to be released from early autumn of 1919 onwards, and the vast majority left Polish camps in December 1919 and January 1920 after declaration of an amnesty by the cabinet of ministers of the Polish Republic (14 December 1919). In this case, those to be released had to submit standard applications; characteristically, many of them contain the statement that they “do not admit to any guilt” and were requesting to return to their parish.[24] Also in line with this regulation, all the confined priests returned to their parishes, with few exceptions.[25] Their relatively swift releases came as a result of a foreign ministry intervention in response to the aforementioned rumours of 600 imprisoned priests, which made a bad impression in the Holy See (their internment supposedly deprived several tens of thousands of believers of the possibility of religious ministration). The Presidium of the Council of Ministers therefore asked the military affairs ministry to release the priests as soon as possible.[26]

Only in autumn 1920 did the Greek Catholic Metropolitan Ordinariate appeal to the Prime Minister to release the clerics from Tuchola: the request was sent to the Ministry of Military Affairs on 26 November 1920,[27] and on 11 January 1921 the ministry issued an order that they be sent home to be able to complete their theological studies. Those affected were Vasyl Kedrynsky, Ivan Pidzharko, Avhustyn Tsebrovsky, Vasyl Grodzky, Ivan Chekasky, Ostafiy Vesolovsky, Petro Verhun, Volodymyr Hrushkevych, Stanislav Dasho, Mykhailo Vorobiy, Yurko Yuzhvyak, Myron Matinka, Hryhoriy Kulyshyts, Pantaleimon Saluka, Mykola Strelbytsky, Andriy Dorosh, Mykhailo Khuda, Osyp Leshchuk, Osyp Haidukevych, Roman Treshnevsky, Mykhailo Pashkowski, Petro Babyak, Mykhailo Felytsky and Nestor Pohoretsky.

However, not all the priests remained in the camps until their release. On 13 April 1919, Fr Marko Gil, a parish priest from Uhnów (Uhniv), Rawa Ruska (Rava-Ruska) district, escaped from Dąbie. He was four days away from being released with the others. An arrest warrant was issued for Gil, but he evaded capture. In January 1920, the Polish authorities still did not know his whereabouts.[28]

It is important to note that internment and being sent to a camp often meant financial ruin for priests. Once they had left their parish, the diocese consistory had to designate a replacement, meaning that interned or confined priests lost their income – which also applied to their families. For example, Fr Teodor Klish, a parish priest from Wołkowyja, Lesko district, applied in 1920 for the parish of Ustianów in the Ustrzyki decanate, stating that he “had been morally and materially destroyed by the Polish-Ukrainian War, having spent four months in the military court prison in Przemyśl and Dąbie, and having almost all [his] economic possessions taken away”.[29] Some priests, following their return from the camps, used their sermons to express their indignation, thereby worsening relations with the Polish population as well as “disturbing public order”. As a result, in March 1920, the presidium of the governorship recommended paying special attention to such priests and reporting any conduct of this kind.[30]

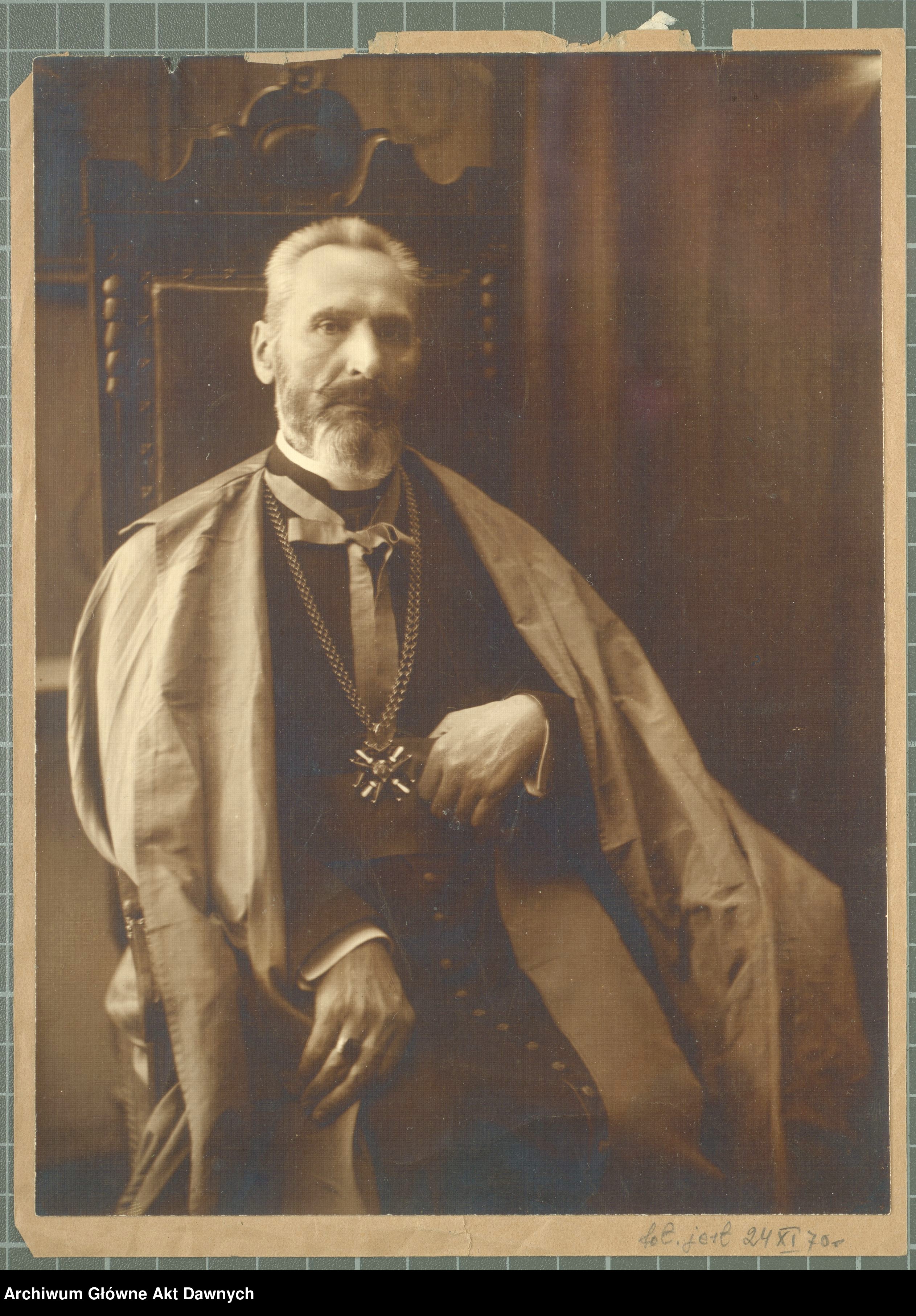

The imprisonment in camps for interned Greek Catholic priests can also be explored from the perspective of several individual stories. The first case is that of Constantine Bohachevsky. This was a significant figure in Przemyśl’s religious life: in 1910, he became a doctor of theology, he was an advisor of the Lwów Metropolitan Consistory, and from June 1918 a priest of the cathedral church, dean and professor of the Przemyśl seminary.[31] On 20 June 2019, he was arrested by the military police in Przemyśl (as well as being searched and having his wallet containing money and prayer book confiscated) and then sent to the prisoner muster station in the Zasanie neighbourhood. Bohachevsky claimed that he was treated very harshly – he was not allowed to go for a walk or to the church to lead a service, nor was he permitted to be given a pillow and blanket brought from home.[32] The priest also said that he had been arrested without cause and without a report being filed. This was not entirely true – he was interned on the orders of the Przemyśl district authority office, which ordered his immediate internment in Zasanie. The Polish authorities claimed that the reason for his arrest was “the priest’s radically chauvinist approach”. After internment, Bohachevsky twice refused interrogation in Polish, despite speaking and writing the language fluently. The internment was also motivated by his function as Greek Catholic parish priest for Przemyśl and his subsequent extensive connections among Ukrainian residents.[33] The specific reason was the matter of a UGCC priest requesting a change from the Greek Catholic to the Roman Catholic rite, a petition that was submitted to the Polish authorities, bypassing the official Greek Catholic Church channels. Bohachevsky did not agree to the change and was therefore summoned to the district authority. There he indeed spoke in Ukrainian, citing Austro-Hungarian law, to which the official apparently replied that he wouldn’t “speak this swine’s language”. Bohachevsky therefore demanded that a report be filed, but since it was filed in Polish he refused to sign it and left the office.[34] On 27 June, Bochachevsky was escorted to the station and sent to the camp in Modlin.[35] In his application for re-examination of his case, he also complained about how he had been transported: “in Przemyśl, two soldiers led me strongly down the middle of the street at noon, and to Modlin one soldier strongly in a third-class carriage”.[36] Upon arrival at the camp in Modlin (probably in early July), he was placed in the work house, where he complained at not receiving the books he needed for his academic work as well as receiving the same provisions as privates (he received victuals in line with the “E” meals table, designated for prisoners-of-war), leaving him weakened. This was not true: the Modlin camp commander, Maj. Jerzy Lambach, reported that Bohachevsky had access in the camp to his own religious and academic books, and should he need more there was nothing to prevent them from being provided. The major pointed out that Bohachevsky was hostile to the Polish authorities.[37] Despite this, he wrote to Piłsudski demanding to be released and to be able to return to Przemyśl or permitted to go to Krakow. The Chief of State’s civil chancellery interpreted the application in an interesting way, concluding that Bohachevsky had not been interrogated. The response was meticulous: the officials wrote to the Polish Army Supreme Command (PASC) and to the Modlin Fortress command with three questions: 1) For what reason and on whose orders had the applicant been interned? 2) Was it advisable to relocate him in a larger city? 3) Would it be possible to relax the strictness of the applicant’s stay in Modlin so that he could receive the books essential for his academic work? In response, letters arrived from the Modlin Prison Camp Command (discussed above) as well as the Ministry of Military Affairs, which sent the priest’s application to the internee release review board in Krakow requesting an immediate enquiry into the matter; the civil chancellery was also to be notified of the result.[38] I am not aware of the outcome, but it is likely that the chancellery was satisfied with the explanations sent from Modlin. On Military Affairs Ministry order No. 5947/Mob. from 17 July 1919, Fr Bohaczevsky was sent to Dąbie. It is worth adding that Bp Kotsylovsky intervened regarding his release as early as late June 1919 in Lwów, when he and Abp Sheptytsky lodged a protest against the priest’s internment.[39] On the way from Modlin to Dąbie, Bohachevsky secured an audience with the papal nuncio, Achille Ratti, who in a letter to Gen. Haller criticised the Poles for creating a system that “persecutes such heroes” as Bohachevsky.[40] This resulted in an intervention from the Vatican that led to Fr Constantine Bohachevsky’s release from Dąbie on 1 September 1919. He returned to Przemyśl 21 days later, ceremoniously welcomed by the city’s Ukrainian population.[41]

A further typical example of a priest interned in the early period of the Polish-Ukrainian War was Fr Teodor Yarka. He was arrested on 24 November 1918 in his parish in Boratyn during a service and searched for weapons in the church. Fr Yarka was then taken to a detention centre in Jarosław, from which he was sent to Krakow on 27 November. He was detained there for 24 hours before being transferred as an internee to the Central Hotel on Warszawska Street (where he lived with Dr Teofil Kormosh and other internees from Przemyśl). In his application to the Przemyśl consistory, Yarka stated that the reason given for his arrest had been “incitement of the Ruthenian nation” and insulting Polish state officials.[42] After a few days, he was summoned to the prosecutor’s office, where he was charged with insurrection. On the request of the prosecutor, he was sent to a detention centre for 38 days, before being transferred as an internee to Dąbie.[43] The priest was also attacked by the Polish press.[44] On 15 February 1919, parishioners from the three municipalities of the Greek Catholic parish of Boratyn – Boratyn, Dobkowice and Tapina – lodged an appeal for the priest’s release from internment. This was motivated by the fact that their parish priest was in the camp “as a victim of social upheaval, not his own fault”, which was supposedly proved by the investigation of the military and civilian authorities. Blame was apportioned to a certain Ignatsy Gamratsy, who upon his return from captivity in Russia had come to the presbytery and praised the Bolshevik orders, for which the priest had admonished him. In response, Gamratsy had apparently spread rumours against him. The parishioners insisted that the priest was irreproachable in political terms and treated Poles, Ukrainians and Jews equally. They also emphasised that the people had been left without a “spiritual father” and had nobody to administer sacraments (funeral, christenings), while schoolchildren were unable to learn.[45] The matter was referred elsewhere, as on 15 March 1919 the Jarosław district authority categorically opposed the priest’s release due to his “activity after the fall of Austria-Hungary”. This was also about ensuring peace in the operational territory.[46] However, Fr Teodor Yarka was released from Dąbie on 14 April 1919, and a day later he returned to Boratyna. On 10 April 1919, the Przemyśl military district command ordered an investigation from the local military police branch, which on 30 April 1919 referred the case to the Jarosław military police. On 7 May 1919, the Jarosław military police branch office enquired with the Chłopice branch as to whether Fr Yarka had been freed from the camp, and if not, whether there were any obstacles to his release.[47] Evidently the flow of information in the army was deficient as only the lowest authority, the local station, was informed that the priest was free.

A rather typical example of a Greek Catholic clergyman interned in the second half of 1919 was Fr Ilya Klyvak, who arrived in the parish of Jazłowiec (Yazlovets) in October 1918. After the change in government – according to witnesses he was a “confidant” of the Ukrainian government – he can be said to have enjoyed good relations with the district commissioner in Buczacz (Buchach), Ilarion Botsiurkiv. He apparently intervened in the cases of Poles interned in a camp in Jazłowiec, agitated the Ukrainian population against Poles, and was also involved in the matter of the local Raiffeisen credit union, which the Ukrainian authorities wanted to take control of. During the Polish offensive in May 1919, he supposedly encouraged people to join the Ukrainian army.[48] In a letter to the district commissioner, he wrote, “to let the poor rabble go home after strict reprimands and send the fatter Poles to Poland because the town is screaming that our enemies are eating our bread […] Here is what I offer for consideration”.[49] Given this stance and the state of political relations in the Buczacz district (recently liberated from Ukrainian rule), on 1 September 1919 a motion was submitted for Fr Klyvak to be interned in a camp outside of Galicia. This order was carried out.[50] Fr Ilya Klyvak was sent to the camp in Dąbie, returning only after the amnesty in January 1920.

An untypical example of an interned Greek Catholic priest was Fr Mykhailo Kit. Interned in Brest-Litovsk on 14 February 1919, he was then transferred to Szczypiorno. According to his letter, he was arrested solely for being Ukrainian. In fact, however, he settled in Brześć of his own accord, without permission from Metropolitan Sheptytsky, and – apart from religious matters – he engaged in pro-Ukrainian and anti-Polish propaganda. Following Nuncio Achille Ratti’s intervention with Piłsudski, he was transferred to Warsaw and placed in the Capuchin monastery there. Kit’s presence caused big problems: as the monastery was too poor to feed him, the military affairs ministry’s economic department had to pay his bills. Furthermore, the priest was given a large amount of freedom, receiving illegal correspondence and contacting his family. In September 1919, he freely went into the city and met whom he wanted as the Capuchin provincial superior believed that “no orders except for those of God and his ecclesiastical authorities apply”. As a result, in September 1919 the military affairs ministry wrote to the PASC requesting an investigation of the reasons for his internment and his potential release.[51]

A separate case was that of Fr Volodymyr Lysko. From 1918, he was the administrator of the parish of Gródek Jagielloński (Horodok), where he was arrested on 3 December 1918 and sent to Lwów. According to records from 1919, the priest was sick at the time, and Polish soldiers dragged him out of bed with a fever of 39 degrees. He ended up in Lwów, where he was put in the Krakowski Hotel with a guard stationed outside his room. As Lysko recalled many years later, he was not treated badly in terms of food (with meals brought from the officers’ kitchen), yet the stay in a small room had an adverse effect. On 13 December 1918, on the request of Abp Józef Bilczewski (notified by Dean Moczarowski) and the orders of Gen. Rozwadowski, the prisoner was released.[52] Fr Lysko was arrested for a second time on 21 May in Gródek. He was then interned for several months in Dąbie. He escaped captivity thanks to a fortunate coincidence: his father-in-law, the papal chamberlain Mykhailo Tsehelsky, was to have an operation, which was not entirely safe owing to his advanced age, so Fr Lysko requested a temporary release. It so happened that the Dąbie internee camp commander at the time, Lt Col Stefan Galli, had once served in Gródek, which was the priest’s explanation for being given eight days’ leave. This was then extended thanks to a Polish Army doctor – a Jew who issued him with a certificate stating that he was too ill to travel.[53] Yet this situation continued as Lysko paid visits to the head of the Gródek district authority for permission for confinement there on the grounds that the stay in Dąbie had ruined him financially. He did not agree at first, and Lysko responded by saying he would demand an investigation from the governorship, for which he was arrested and harassed. The district head then agreed to his confinement, not in the parish but in a rented apartment in Gródek Jagielloński.[54] Fr Lysko therefore never returned to the camp.

A case that sent shockwaves around not only Poland but also the Vatican was the internment of all the residents of the Basilian monasteries in Żółkiew and Krechów. At 5:30 p.m. on 20 May 1919, the monastery in Krechów was entered by military police under the command of Second Lt Mroczkowski. All the monks had their details taken and the monastery was confiscated. They were then taken to a detention centre in Żółkiew, where the monks from the Żółkiew monastery were already being held. Altogether, 44 Basilians were detained (11 from Żółkiew and 32 from Krechów).[55] The internment was carried out on the orders of Col. Minkiewicz. As the garrison command in Rawa Ruska explained, “the Basilian fathers used to be famous for agitation, and today the Ruthenian priests and clerics are still famous for it. By giving boisterous and chauvinistic sermons and calling to ‘fight the Poles’, and not having, as priests should, a calming influence on the Ruthenian soldiers and not protecting the population from looting”.[56] We can therefore conclude that they were arrested for anti-state agitation. Nevertheless, the camp command was unaware of the specific reason for the internment as the Basilians had been sent to Dąbie without any explanations (the above justifications were only given on 9 June, whereas the monks arrived in the camp on 24 May). The information about their hardship in Dąbie is probably somewhat exaggerated: Abp Bilczewski noted that these clergymen wrote in a letter to their superior in Lwów that “things are not too bad” (he asked the archbishop for help in getting them out of the camp).[57] In Dąbie, they immediately embarked on pastoral work, celebrating mass and hearing confession.[58] News of the internment of the Basilian fathers quickly spread – word of the events in the two monasteries reached Przemyśl, where the Church authorities made efforts to secure the monks’ release. Metropolitan Sheptytsky wanted Bp Kotsylovsky to travel to Warsaw and resolve the matter with Nuncio Ratti, but for various reasons the Przemyśl bishop decided against doing so in person.[59] However, the nuncio received a letter from the internees in Dąbie and decided to act in person. Although his intervention with Bp Sapieha was unsuccessful, his efforts got things moving, and in early August the Basilians left the camp in Dąbie (at a time when an American delegation was visiting).[60] In fact, the military affairs minister had already released the Basilians (order No. 3541/Mob. of 13 June 1919) and ordered that they be confined in the Capuchin monastery in Sędziszów, but for some reason this had not been carried out.[61] On 4 August 1919, the Basilians were divided into four groups: the first was sent to Nowy Sącz (Jesuit monastery, 12 people), the second to Zaliczyn (Reformed monastery, seven people), the third to Kęty (Reformed monastery, 15 people), and the last to Mogiła (Cystersian monastery, 10 people).[62]

On 29 August 1919, the Ministry of Military Affairs asked the PASC to send precise explanations due to the interest of the Apostolic Nunciature. The ministry repeated the request for detailed materials on the Basilians’ internment on 13 September 1919, deeming the explanations from 13 August 1919 (letter No. 31608/IV) insufficient. The Quartermaster of the Galician Front Command had reported on 22 August 1919 that the monks’ agitation meant that their return was inadvisable. However, the ministry, facing difficulties with placing the Basilians in monasteries in Western Galicia (protests from those in charge), decided that the only solution would be to confine the monks in their own monasteries in Żółkiew and Krechów, and possibly in Ławrów (Lavriv), Stary Sambor (Staryi Sambir) district, under the strict control of state and military police.[63] The PASC replied in September 1919 that, apart from hostile agitation carried out in the district by the Basilians, it had no other information on the reasons for their internment. The Supreme Command accepted the ministry’s proposal regarding where to send the monks.[64] The Basilians finally returned to their monasteries in mid-September 1919 (Fr Stepan Reshetylo stated that they were freed on 18 September 1919 and the next day were back in Krechów).[65]

The internments of Greek Catholic priests in Galicia were wide-ranging. The Polish authorities imprisoned at least 170 clergymen for varying lengths of time. The first appeared in camps as soon as December 1918, yet the most extensive operations took place as the Polish armies occupied further areas of Eastern Galicia in May, June and July 1919. From the Polish authorities’ point of view, this was dictated by the need to extinguish the harmful agitation that priests were spreading among their parishioners; indeed, most of the arrests were made on genuine grounds. Internment also affected priests who in the ZUNR period participated in the construction of Ukrainian statehood or displayed a negative attitude towards Poles. Nonetheless, there were also cases in which harmless priests were detained, which strained Poland’s image in the international arena. Ukrainian propaganda exploited these facts, harming the Polish cause, particularly in Rome (where representatives of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church gave significantly exaggerated data on those interned and confined). The internment of two entire Basilian monasteries in Żółkiew and Krechów had negative repercussions, despite some justifications (it is worth emphasising that the monks in Żółkiew printed sheets of ZUNR documents, UGA newspapers and other such publications). Releases of the internees took place in several stages, first in response to analogous releases of Roman Catholic priests in the ZUNR, then following the intervention of Nuncio Ratti, and finally in autumn and winter 1919/1920 as a result of the Polish government amnesty.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ARCHIVE SOURCES:

Central Military Archive (CMA):

ref. I.301.10.334

ref. I.304.1.26

ref. I.310.1.36

ref. I.310.1.41

ref. I.310.2.26

Central Archives of Modern Records (AAN)

KCNP, ref. 285

MFA, ref. 5336

Polish Embassy in London, ref. 447

PRM, Numerical files, ref. 687/21

Przemyśl State Archive (AP), Greek Catholic Bishops Archive (ABGK):

ref. 4417

ref. 4721

ref. 4731

Ivano-Frankivsk District State Archive (DAIFO):

f. 11, op. 1, spr. 3, l. 1

National Archives, Kew, FO 608/59

Tsentralʹnyj deržavnyj istoryčnyj archiv Ukrajiny u misti Lʹvovi (Central State Historical Archive of Ukraine in Lviv, TsDIAL):

f. 146, op. 8, spr. 3043

f. 212, op. 1, spr. 202

f. 214, op. 1, spr. 618; spr. 620

f. 309, op. 1, spr. 2636

f. 358, op. 1, spr. 171

f. 684, op. 1, spr. 2033

SECONDARY LITERATURE

‘Agitatorzy i szpiedzy ukraińscy pod kluczem’,

Goniec Krakowski, 75 (20 March 1919)

Bohachevsky-Chomiak, Marta, Ukrainian Bishop, American Church, Constantine Bohachevsky and the Ukrainian Catholic Church (Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 2018)

Hajova, Oksana, Uljana Jedlinsʹka and Halyna Svarnyk, eds, U pivstolitnich zmahannjach. Vybrani lysty do Kyryla Studynsʹkoho (1891–1941) (Kyjiv: Naukova dumka, 1993)

Hentoš, Liliana, Vatykan i vyklyky modernosti. Schidnojevropejsʹka polityka papy Benedykta XV ta ukrajinsʹko-polʹsʹkyj konflikt u Halyčyni (1914–1923) (Lʹviv: Klasyka, 2006)

Korduba, Myron, Ščodennyk 1918–1925 (Lʹviv, Ukrajinsʹkyj Katolycʹkyj Universytet, 2021)

Kormoš, Teofil, ‘Spomyny z ostannych dniv (prodovžennja)’, Republyka, 19 (23 February 1919)

Kormoš, Teofil, ‘Spomyny z ostannych dniv (prodovžennja)’, Republyka, 20 (24 February 1919)

‘Kronika: za wzywanie do rzezi Polaków’, Kurier Lwowski, 531 (7 December 1918)

Kupčyk, Lidija, Bez zerna nepravdy: Spomyny otcja-dekana Volodymyra Lyska (Lʹviv: Kamenjar, 1999)

‘Naše hromadjanstvo povitalo…’, Ukrajinsʹkyj Holos, 25 (28 September 1919)

O. Lebedovyč, Іvan, Polevi duchovnyky UHA (Vinnipeh, 1963)

Pagano, Sergio and Gianni Venditti, eds, I diari di Achille Ratti, I, Visitatore Apostolico in Polonia (1918–1919) (Citta del Vaticano: Archivio Segreto Vaticano, 2013)

Paska, Bohdan, ‘Kostjatyn Bohačevsʹkyj’, in Zachidno-Ukrajinsʹka Narodna Respublika. 1918–1923. Encyklopedija, 4 vols (Іvano-Frankivsʹk: Manuskrypt-Lʹviv, 2018–2021), I (2018)

‘Polʹsʹki vlasty vypustyly…’, Ukrajinsʹkyj Holos, 22 (7 September 1919)

Sribnjak, Іhor, Encyklopedija polonu: ukrajinsʹka Tuchola (Kyjiv: Mižnarodnyj naukovo-osvitnij konsorcium imeni Ljusʹjena Fevra, 2016)

Szczupak, Adam, ‘Polityka państwa polskiego wobec kościoła greckokatolickiego w latach 1918–1919 na przykładzie eparchii przemyskiej’, Rocznik Przemyski. Historia, 55.4(24) (2019), 89–108

Szczupak, Adam, Greckokatolicka diecezja przemyska w latach I wojny światowej (Kraków: Historia Iagellonica, 2015)

Szczupak, Adam, ‘Polityka państwa polskiego wobec Kościoła greckokatolickiego w latach 1918–1923’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Uniwersytet Jagielloński. Wydział Historyczny, 2020)

Węglewicz, Wiktor, ‘Wspomnienia Teofila Kormosza z działalności w Ukraińskiej Rady Narodowej w Przemyślu i pobytu w obozie internowanych w Dąbiu (październik 1918 – styczeń 1919 r.)’, Rocznik Przemyski. Historia, 55.4(24) (2019), 243–78

Wołczański, Józef, ed., Kościół rzymskokatolicki i Polacy w Małopolsce Wschodniej podczas wojny ukraińsko-polskiej 1918–1919. Źródła, 2 vols (Lwów–Kraków, 2012)

[1] Adam Szczupak, ‘Polityka państwa polskiego wobec kościoła greckokatolickiego w latach 1918–1919 na przykładzie eparchii przemyskiej’, Rocznik Przemyski. Historia, 55.4(24) (2019), 89–108 (pp. 91–92).

[2] Adam Szczupak, Greckokatolicka diecezja przemyska w latach I wojny światowej (Kraków: Historia Iagellonica, 2015), p. 217.

[3] In Austro-Hungarian law, and subsequently in Poland in 1918–1921, confinement was a prohibition on leaving the designated place of stay – in other words, detention in a designated place.

[4] For more, see: Wiktor Węglewicz, ‘Wspomnienia Teofila Kormosza z działalności w Ukraińskiej Rady Narodowej w Przemyślu i pobytu w obozie internowanych w Dąbiu (październik 1918 – styczeń 1919 r.)’, Rocznik Przemyski. Historia, 55.4(24) (2019), 243–78 (pp. 254–58).

[5] Application for internment of Fr Hryhoriy Muzychko, 28 June 1919, Central Military Archive (hereafter CMA), ref. I.310.1.36.

[6] Letter of the Rohatyn District Authority Office in Rohatyn to the PASC Liasion Officer, 8 October 1919, on the internment of Fr Petrytsky, Tsentralʹnyj deržavnyj istoryčnyj archiv Ukrajiny u misti Lʹvovi (Central State Historical Archive of Ukraine in Lviv, hereafter TsDIAL), f. 214, op. 1, spr. 620, l. 64.

[7] Case of Fr Kovalsky from Nowosiółki (Novosilky), September–October 1919, TsDIAL, f. 214, op. 1, spr. 620, l. 24–28.

[8] Szczupak, ‘Polityka państwa polskiego’, p. 92.

[9] Ministry of Foreign Affairs (hereafter MFA) information for Polish envoy to the Holy See, 9 January 1920, No. 738/D.169/I/20, with a response to two Ukrainian memoranda from 1919, Central Archives of Modern Records (hereafter AAN), Polish Embassy in London, ref. 447, p. 3.

[10] MFA information for the Polish ambassador in Rome, 9 January 1920, No. 738/D.169/I/20, with a response to two Ukrainian memoranda from 1919, AAN, Polish Embassy in London, ref. 447, p. 3.

[11] MFA letter to PASC Liaison Officer No. D.15332/V/19, 19 December 1919, on provision of data concerning interned Ukrainians, TsDIAL, f. 214, op. 1, spr. 618, l. 58.

[12] O. Іvan Lebedovyč, Polevi duchovnyky UHA (Vinnipeh, 1963), pp. 237–42.

[13] Liliana Hentoš, Vatykan i vyklyky modernosti. Schidnojevropejsʹka polityka papy Benedykta XV ta ukrajinsʹko-

-polʹsʹkyj konflikt u Halyčyni (1914–1923) (Lʹviv: Klasyka, 2006), pp. 253–54.

[14] Letter of Fr Vilchansky to Episcopal Consistory in Przemyśl, 4 August 1919, on the internment of Fr Yaremkevych, Przemyśl State Archive (hereafter AP Przemyśl), Greek Catholic Bishops Archive (hereafter ABGK), ref. 4721, p. 123.

[15] Calculations based on documents from disparate sources, including a list of internees in Dąbie (containing information about the date of their arrival in the camp and sometimes the release date), release requests made to the PASC Liaison Officer to the General Polish Government Delegate in Eastern Galicia, materials of the Greek Catholic Episcopate in Przemyśl and others.

[16] I thank Dr Adam Szczupak for providing me with this information. Adam Szczupak, ‘Polityka państwa polskiego wobec Kościoła greckokatolickiego w latach 1918–1923’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Uniwersytet Jagielloński. Wydział Historyczny, 2020).

[17] Іhor Sribnjak, Encyklopedija polonu: ukrajinsʹka Tuchola (Kyjiv: Mižnarodnyj naukovo-osvitnij konsorcium imeni Ljusʹjena Fevra, 2016), pp. 115, 128.

[18] E.g. Ministry of Military Affairs (MMA) letter to Presidium of Cabinet, L.8626 .B.P.II, 11 January 1921, on the release of Greek Catholic priests, AAN, PRM, Numerican files, ref. 687/21.

[19] Letter from the National Foreign Affairs to Dr Volodymyr Okhrymovych, part 304, 19 March 1919, on the exchange of prisoners-of-war and internees, TsDIAL, f. 146, op. 8, spr. 3043, l. 17–18.

[20] Hentoš, Vatykan i vyklyky modernosti, p. 272.

[21] Ibid., pp. 274. This explains the question in Brygidki of the initial ban and later permission for the priests interned there to lead religious services for their civilian fellow inmates.

[22] Ibid., pp. 274–75.

[23] Myron Korduba, Ščodennyk 1918–1925 (Lʹviv, Ukrajinsʹkyj Katolycʹkyj Universytet, 2021), pp. 285–86.

[24] Applications of Greek Catholic priests for release from internment, AAN, MFA, ref. 5336, pp. 16–23.

[25] MFA information for the Polish envoy to the Holy See, 9 January 1920, No. 738/D.169/I/20, with a reply to two Ukrainian memoranda from summer 1919, AAN, Polish Embassy in London, ref. 447, p. 3.

[26] Copy of MFA letter to the Minister [of Internal Affairs] N-D 13276/V/19, 3 November 1919, concerning interned Greek Catholic priests, TsDIAL, f. 214, op. 1, spr. 618, l. 84.

[27] Summary of letter from the Presidium of the Council of Ministers [December 1920] concerning the release of Greek clergymen from Tuchola, AAN, PRM, Numerical files, ref. 687/21, n.p.

[28] Fr Gil ended up in Czechoslovakia, returning to Poland only in the mid-1920s. Arrest warrant for Fr Gil, 24 April 1919, CMA, ref. I.304.1.26; MFA information for Polish envoy to the Holy See, 9 January 1920, No. 738/D.169/I/20, with a response to two Ukrainian memoranda from 1919, AAN, Polish Embassy in London, ref. 447, p. 3.

[29] Application of Fr Teodor Klish to the parish of Ustianów, 20 July 1920, AP Przemyśl, ABGK, ref. 4731, pp. 19–20.

[30] Letter from the Presidium of the Governorship L. 5626/pr., 6 March 1920, on the agitation of priests released from camps, Ivano-Frankivsk District State Archive (herafter DAIFO), f. 11, op. 1, spr. 3, l. 1.

[31] Bohdan Paska, ‘Kostjatyn Bohačevsʹkyj’, in Zachidno-Ukrajinsʹka Narodna Respublika. 1918–1923. Encyklopedija, 4 vols (Іvano-Frankivsʹk: Manuskrypt-Lʹviv, 2018–2021), I (2018), p. 148.

[32] Application of Fr Constantine Bohachevsky, 22 July 1919, AAN, KCNP, ref. 285, p. 21.

[33] Report of the Prisoner-of-War Muster Station on interns and civilians in Przemyśl for the Justice Officer of the Polish Army Command in Eastern Galicia, 25 June 1919, AAN, KCNP, ref. 285, p. 27.

[34] Marta Bohachevsky-Chomiak, Ukrainian Bishop, American Church, Constantine Bohachevsky and the Ukrainian Catholic Church (Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 2018), p. 76.

[35] Letter of Bp Kotsylovsky to Metropolitan Sheptytsky of 28 June 1919 in response to the metropolitan’s letter, TsDIAL, f. 358, op. 1, spr. 171, l. 24.

[36] Application of Fr Constantine Bohachevsky of 22 July 1919, AAN, KCNP, ref. 285, pp. 21–22.

Strongly = armed and with fixed bayonets.

[37] Report of the commander of Modlin prison camp No. 2645, 1 August 1919, AAN, KCNP, ref. 285.

[38] Enquiry of the Chief of State’s Civil Chancellery No. 2921/19 to the General Staff, 24 July 1919, AAN, KCNP, ref. 285, p. 19; MMA Report Dep. I No. 5947/Mob., 3 August 1919, p. 28.

[39] Letter from Bp Kotsylovsky to Metropolitan Sheptytsky, 26 June 1919, on going to Lwów and correspondence, TsDIAL, f. 358, op. 1, spr. 171, l. 23.

[40] Bohachevsky-Chomiak, Ukrainian Bishop, p. 77.

[41] ‘Polʹsʹki vlasty vypustyly…’, Ukrajinsʹkyj Holos, 22 (7 September 1919); ‘Naše hromadjanstvo povitalo…’, Ukrajinsʹkyj Holos, 25 (28 September 1919). Judge Roman Dmokhovsky spoke at the ceremony, extolling the priest’s martyrdom and presenting him with a valuable trophy from the city’s population. Bohachevsky thanked him and replied that he would fulfil his duty as a faithful son of the nation.

[42] Application of Fr Yarka to the Greek Catholic Consistory in Przemyśl, 3 December 1918, AP Przemyśl, ABGK, ref. 4417, pp 659–61.

[43] Teofil Kormoš, ‘Spomyny z ostannych dniv (prodovžennja)’, Republyka, 19 (23 February 1919); Teofil Kormoš, ‘Spomyny z ostannych dniv (prodovžennja)’, Republyka, 20 (24 February 1919).

[44] The Polish press claimed that the reason for Fr Yarka’s arrest had been his calls for the slaughter of Poles and handing out weapons to Ukrainian peasants. ‘Kronika: za wzywanie do rzezi Polaków’,Kurier Lwowski, 531 (7 December 1918).

[45] Authority application of the municipalities of Boratyn, Dobkowice and Tapina for the release from internment of Fr Yarka, 15 February 1919, CMA, ref. I.304.1.26.

[46] Letter from the Jarosław District Authority to the Ruling Commission Administration Department L. 4503, 15 March 1919, on the release of Fr Yarka, TsDIAL, f. 212, op. 1, spr. 202, l. 16.

[47] Authority application of the municipalities of Boratyn, Dobkowice and Tapina for the release from internment of Fr Jarka, 15 February 1919, CMA, ref. I.304.1.26; Letter of the Polish Army Military Police in Eastern Galicia L.610, 7 May 1919, concerning Fr Yarka.

[48] Transcripts of the testimonies of Fr Jan Niedzielski, Józef Harkasheimer, Franciszek Piórecki concerning Fr Klyvak, CMA, ref. I.310.1.41.

[49] Copy of letter from Fr Klyvak to District Commissioner Botsiurkiv concerning the Raiffeisen credit union, CMA, ref. I.310.1.41.

[50] Application for the internment of Fr Ilya Klyvak, 1 September 1919, CMA, ref. I.310.1.41.

[51] MMA letter to PASC No. 8521/Mob., 13 September 1919, concerning Fr Kit, CMA, ref. I.301.10.334; ‘Agitatorzy i szpiedzy ukraińscy pod kluczem’, Goniec Krakowski, 75 (20 March 1919); I diari di Achille Ratti, I, Visitatore Apostolico in Polonia (1918–1919), ed. by Sergio Pagano and Gianni Venditti (Citta del Vaticano: Archivio Segreto Vaticano, 2013), p. 243.

[52] ‘Doc. No. 17, Letter of Col. Sikorski to Abp Bilczewski concerning the release of Fr Lysko’, in Kościół rzymskokatolicki i Polacy w Małopolsce Wschodniej podczas wojny ukraińsko-polskiej 1918–1919. Źródła, ed. by Józef Wołczański, 2 vols (Lwów–Kraków, 2012), I, pp. 83–84; List of interned Ukrainians in the Dąbie camp outside Krakow, TsDIAL, f. 309, op. 1, spr. 2636, l. 40; Bez zerna nepravdy: Spomyny otcja-dekana Volodymyra Lyska, ed. by Lidija Kupčyk (Lʹviv: Kamenjar, 1999), pp. 58–59.

[53] Ibid., pp. 60–61.

[54] Korduba, Ščodennyk 1918–1925, p. 291.

[55] Chronicle of the Krechów Monastery for 1915–1923, TsDIAL, f. 684, op. 1, spr. 2033, l. 20zv.

[56] Letter of the Garrison Command in Rawa Ruska to the Dąbie Camp, 9 June 1919, concerning interned Basilians, CMA, ref. I.301.10.334.

[57] ‘Doc. No. 21, Passage from the diary of the Latin rite Lwów metropolitan, Abp Józef Bilczewski, on the Ukrainian-Polish War of 1918–1919’, in Kościół rzymskokatolicki i Polacy w Małopolsce Wschodniej, II, p. 439.

[58] Chronicle of the Monastery in Krechów for 1915–1923, TsDIAL, f. 684, op. 1, spr. 2033, l. 21.

[59] Letter of Bp Kotsylovsky to Metropolitan Sheptytsky, 11 June 1919, concerning interned Basilians, TsDIAL, f. 358, op. 1, spr. 171, l. 20–23.

[60] Memorandum of the US Envoy in Warsaw, summer 1919, concerning relations in Eastern Galicia, National Archives, Kew, FO 608/59.

[61] Order of Krakow Regional Military Command No. IV/50086, 18 June 1919, concerning interned Basilians in Dąbie, CMA, ref. I.310.2.26.

[62] Chronicle of the Krechów Monastery for 1915–1923, TsDIAL, f. 684, op. 1, spr. 2033, l. 21.

[63] MMA letter to PASC No. 8629/Mob., 13 September 1919, concerning the interned monks from Żółkiew and Krechów.

[64] Summary of PASC response to MMA No. 44253 of September 1919 concerning the Basilian fathers from Żółkiew and Krechów, CMA, ref. I.301.10.334.

[65] ‘Letter № 371, of Fr Stepan Reshetylo to Kyryl Studynsky, 20 November 1919’, in U pivstolitnich zmahannjach. Vybrani lysty do Kyryla Studynsʹkoho (1891–1941), ed. by Oksana Hajova, Uljana Jedlinsʹka and Halyna Svarnyk (Kyjiv: Naukova dumka, 1993), p. 348.